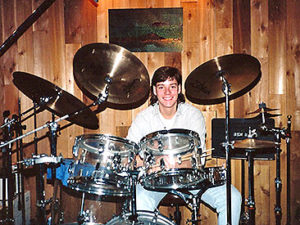

Jason Gerling, The Wheelchair Drummer: Part 1

Jason isn't a BraunAbility product owner, but he became a friend to the company in the late 2000's and his story was one we knew we wanted to share to a broader audience. Hopefully, the advances he's made in the music industry inspire a new generation of artists to do the same.

Read Part 2 of Jason's story here.

Deputy Luther Klug was patrolling the back roads in Hastings, MN. This particular one was dark and empty, with the exception of one car in the middle of the road. It was immediately evident that the car had been rolled. This had happened when Jason had fallen asleep; he had driven across the road to the shoulder and then woken up just enough to try to correct his error. Investigators would later say his car rolled five to seven times before it came to a stop in the road.

There were drum cases and glass shards strewn randomly across the asphalt like some sort of morbid confetti. Klug, a drummer himself, quickly released his seat belt and ran over to the vehicle. There, he found a young man buckled into the driver's seat with blood running down his face and neck. Jason's head laceration was so gruesome that Klug would later say it looked as though he had tumbled out of his life and into a horror movie.

Luther could see there was no way of getting Jason out of the vehicle. Noticing that Jason was struggling to breathe, he quickly pulled an oxygen mask from his police car and pressed it to Jason's face.

The Dotted Line

Jason drifted in and out of consciousness at Regions Hospital in St. Paul. When his mother showed up, she saw her son lying shirtless in a hospital bed, with a dotted line across his chest.

The medical examinations revealed that Jason had a decompressed skull fracture, a collapsed lung, and a spinal contusion between his C6 and C7 vertebrae.

When the Truth Sets In

Between March 27 and May 18, Jason didn't have a lot of time alone to think about his new circumstances. It wasn't until he returned to his parents' house for a home visit that his new reality really sank in.

As he was wheeled up to his parents' front door, he remembered clearly walking through it on two legs to put the last of his equipment into the car before driving to his gig two months prior. Now, he'd never pass through that door, so familiar to him, in that way again. In the entryway, he was hit with the smell of freshly baked bread, a smell he'd thought about in the hospital as he imagined returning home. In his dark-blue bedroom that night, the enormity of life from now on lay heavy on his chest, right at the level of the dotted line.

"I lost it. Tears were streaming down my face and I was like, 'Oh no. I'm never going to play drums again. I don't know how I'm going to do this,'" he said.

"Everyone always knew me as 'Happy Jason.' I was always pranking and joking. And I didn't want anyone to see a negative side to me so I kept it very quiet."

He was given over to the care of a psychiatrist. He remembers her saying, "Jason, you are going to experience a lot of hardship with this. And I want to encourage you, Jason, to talk about it."

"And I told her, 'I'm fine,'" barely being able to squeeze such a huge lie through his teeth.

The depression continued and got deeper; so did the counseling. Sometimes he'd imagine how he'd end his life and get out of the dark spot he was in. The solution to happiness, the psychiatrist said, was not to bottle up the emotion. Rather, Jason was instructed to tell his friends and his family how he felt and to accept it.

Eventually, he continued outpatient therapy at the Courage Kenny Rehabilitation Institute, and it was here that he was first approached about speaking events.

Jason wasn't sure at first. What could he possibly say? He was a depressed, paralyzed kid whose dreams of traveling the world seemed to be over. Still, after encouragement from his therapist, he began to talk at disability awareness events. From there, Regions Hospital invited him to speak events held for the emergency responders and local high schools. Then he began speaking at churches. Jason recommitted his life to Christ and leaned heavily on his faith to help him through these trying times. With every recitation of his favorite verse (Philippians 4:13 "For I can do everything through Christ, who gives me strength,") a part of his soul was healed. And with every event he spoke at, a piece of himself returned.

Finding His Forever

It was during one of these events that Jason saw his now-wife, Bobbi. She was sitting in a church audience as Jason retold his story. It wasn't love at first sight, because it wasn't first sight at all: at school, Bobbi's best friend, Genie, was Jason's best female friend. Genie used to joke about Bobbi and Jason eventually dating, but, at the time, they were both involved with other people. Still, Jason couldn't help but scroll a note on the back of one of his high school pictures: "If you ever break up with your boyfriend, let me know," complete with a drawn-on smiley face.

So when Jason saw Bobbi, it was really like finding a friend again. He'd been dumped recently by his first girlfriend after the accident because her family hadn't approved. He'd lost friends that he thought would be there for life. But in Bobbi, he'd finally found a friend, and eventually, a partner for life. They were married in 1997.

Things were going well with counseling for Jason. Being able to have serious conversations with kids in church youth groups and in schools gave him a release. Then, his therapist suggested Jason may want to consider going back to school.

"She said, 'Your drumming career might be over. You need to be realistic about this.' And I said, 'I don't want it to be over.' So I had two big choices on my mind: college or drumming."

To Jason, drumming was still a very painful subject even to think about. Looking at the sheen off the kit's cymbals under the overhead light in his parents' basement was nearly impossible without thinking of the ruined set strewn across the dark road stained with his blood. Regretfully, he says, he sold his set to pay for college classes, and would have sold a second set he had built by hand if his father hadn't persuaded him otherwise.

For his father, the pain he saw in his son's eyes was hard to bear, but deep down he knew Jason would get back to his drumming.

Jason completed an associate degree in electronic publishing and pre-press in 1999. He then entered the corporate world. But before long, Jason went back to his drums.

Other Owner Stories:

- Zach Anner

- Adam Gorlitsky

- Mike Delancey

- Jesse Billauer

- Rachelle Chapman

- Reveca Torres

- Robin Allen

- Travis Roy

- Ben Trockman

- Young Customer Gives BraunAbility an A+ Grade

- Wheelchair Vans: Five and Counting!

- Wheelchair Van Reliability Gets a Real World Test

- Wheelchair Marathoning: 50 marathons in 50 states in 50 weeks

- Wheelchair Van Donation Changes Kentucky Family's Lives

- Wheelchair Accessible Van is the Answer to Grandparents' Prayers

- Fishing and Wheelchair Vans

- The Truth About Living with a Rare Disease

- Tom Turner's More Than 30 Years of Friendship

- Third Spirit of Ability Recipient Honored in Toronto

- Spirit of Ability Winner Triumphs over SCI

- Sam Schmidt to Help Unveil New Hand and Foot-Free Corvette

- Sam Schmidt: Mobility Visionary and Real-Life Superman

- A Rampvan for a Pharmacist and Her Service Dogs

- "Praise the Lowered?" Absolutely!

- Wheelchair Van Funding: Patience and Persistence Pay Off

- Paralyzed Coach Receives Wheelchair Van at Halftime

- Barbara's New Rampvan: Taking Delivery

- Neural Prosthetics Got Her On Her Feet Again

- My Road to Driving Independence

- Mother With a Disability Finds Hope in Two Disabled Sons

- Meet Spirit of Ability Award Winner Barry Munro

- Life Happens Together, Just Ask Lauren Gross

- Lacrosse Team Scores Big for a Deserving Family

- Jason Gerling, The Wheelchair Drummer: Part 2

- Jason Gerling, The Wheelchair Drummer: Part 1

- Indiana Family Proud Owners of a Honda Entervan

- In the Company of Saints

- Home On the Range and In a Tri-Wheeler

- Head Coach of Team USA Wheelchair Rugby Team Trusts BraunAbility

- "Freedom" by Scott Drotar

- Restoring Freedom For Loyal BraunAbility Customer

- First Entervan XT Owner is eXTra happy!

- Family with Three Wheelchair Users Gets First Accessible Van

- ESPN's Story "Picking Up Butch" Gets National Media Attention

- Driving Freedom For a BraunAbility Customer